The next town over from us, Loveland, Colorado, boasts a number of sculptures in its adorable little downtown nooks. Each one has the name of the piece, the artist, and a brief description of its materials embossed on a copper sign posted on the knee wall around the sculpture. Also on the sign is the same information in Braille.

Now this is strange. First of all, the blind would need to know there was a sculpture nearby, which comes with obvious problems. Secondly, for the blind person to read the Braille inscription, they would need to grope around the foot of the sculpture to find the placard. This means, if they are to know a sculpture is nearby, someone with sight would need to tell them about the placard, at which point, why wouldn’t this guy just read the description to them, or at least describe the piece, instead of watching them just grope around like a baby raccoon for an hour? Warmer, warmer, WARMER!…oh, colder. Jerk move, dude.

That is an odd introduction and only obliquely pertains to what I intended to talk about here. But it does have blind people in it, so you can at least see the thread.

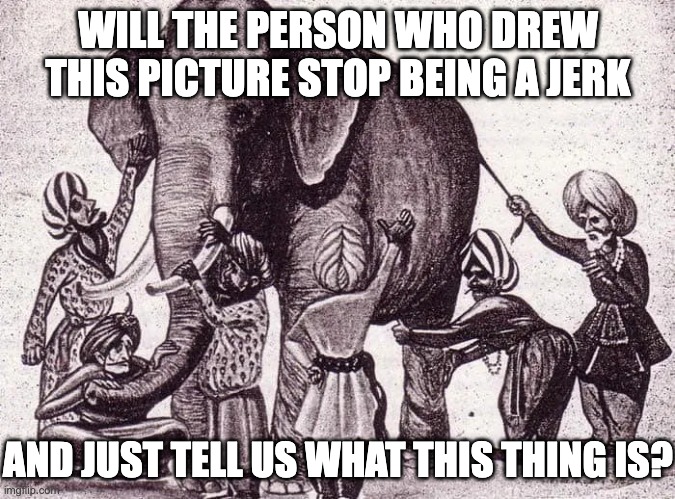

There is old Indian tale of blind men who stumble upon an elephant. You have heard it. Here is a version I ripped off the web.

There were once six blind men who stood by the road-side every day, and begged from the people who passed. They had often heard of elephants, but they had never seen one; for, being blind, how could they?

It so happened one morning that an elephant was driven down the road where they stood. When they were told that the great beast was before them, they asked the driver to let him stop so that they might see him.

Of course they could not see him with their eyes; but they thought that by touching him they could learn just what kind of animal he was.

The first one happened to put his hand on the elephant’s side. “Well, well!” he said, “now I know all about this beast. He is exactly like a wall.”

The second felt only of the elephant’s tusk. “My brother,” he said, “you are mistaken. He is not at all like a wall. He is round and smooth and sharp. He is more like a spear than anything else.”

The third happened to take hold of the elephant’s trunk. “Both of you are wrong,” he said. “Anybody who knows anything can see that this elephant is like a snake.”

The fourth reached out his arms, and grasped one of the elephant’s legs. “Oh, how blind you are!” he said. “It is very plain to me that he is round and tall like a tree.”

The fifth was a very tall man, and he chanced to take hold of the elephant’s ear. “The blindest man ought to know that this beast is not like any of the things that you name,” he said. “He is exactly like a huge fan.”

The sixth was very blind indeed, and it was some time before he could find the elephant at all. At last he seized the animal’s tail. “O foolish fellows!” he cried. “You surely have lost your senses. This elephant is not like a wall, or a spear, or a snake, or a tree; neither is he like a fan. But any man with a par-ti-cle of sense can see that he is exactly like a rope.”

Then the elephant moved on, and the six blind men sat by the roadside all day, and quarreled about him. Each believed that he knew just how the animal looked; and each called the others hard names because they did not agree with him. People who have eyes sometimes act as foolishly

James Baldwin, The Blind Men and the Elephant

This tale is often used as some kind of tai chi move to parry the thrust of a person proclaiming to know the truth on a subject, mostly about God. Often the person is a Christian, as there aren’t many too many in post modernity with the cajones to speak authoritatively on spiritual matters. Its a pandering move, to be sure, and the point is that the Christian is just one blind man among many attempting to make sense of his blind fumblings. The moral of the story is that all of us all humans are equally searching for truth but each is only able to understand the portion he has been given. World religions are so many blind men feeling up elephants, and so we ought to have some epistemological humility when it comes to dogmatic claims of truth.

Not everyone is so blind to the truth, however. There is a seventh man. Did you spot him? It’s the storyteller, off the page, sitting on his throne of omniscience, the only one who magically has objective knowledge of what is happening when everyone else is blinded by their limited perspective. And the weasely thing about this bloke is he uses his position of absolute truth to tell a story, the moral of which is that there is no absolute truth. He alone can testify to the truth and all the rest of us are aboriginals molesting pachyderms.

Most irritatingly, in my experience, is when the spirit of this parable is used by the woke. I am told the term ‘woke’ is frustrating to those who are woke, as it seems like a pejorative, which kinda makes me want to use it more, if I am being honest. But I also have a high value for originality, so how about we use Big Virtue. You know, like Big Pharma, Big Insurance, Big Tobacco each have a strangle hold on their market and use their influence to control lives, the wokies presume to have a corner on the virtue market controlling what people say and do.

Where was I? Oh yes, Big Virtue, in our time, is the seventh man. It presumes to know the deeper reasons why we all do certain things based on presumptions that remain unchallenged. That is why you undergo “unconscious bias” training at work – you may not know why you say or do certain things, but they can see deep into the caverns of your unconscious to know what you really think.

Whenever someone takes the liberty of rewriting your history for you, like has been done in The 1619 Project, beware the seventh man. They are taking a position of absolute truth, of an omniscient narrator, like an author, who knows the motivations of all the characters but themselves are subject to no narration. Taking the liberty to redefine all motivations of complex individuals with varied lives and collapsing it into a series of Marxian dualisms – proletariat/bourgeoisie, black/white, oppressor/oppressed – all while perched atop an ivory tower of virtue, is about as seventh man-ish as it gets.

Now some astute reader may say, “Isn’t Christianity also a seventh man? Doesn’t it think it is the one who has the truth and all others are the fumblers, seeking the truth?” Two answers to this. One, yes it does. That is what a religious worldview does – makes claims of absolute truth and applies that truth to the whole world. Which is why Big Virtue is a religious worldview. Secondly, Christianity claims that men are not feeling around the same truth just getting different answers, but that they know they truth and work to suppress it.

The Christian knows that there are no ‘blind men’ spiritually. As Paul made abundantly clear

For the wrath of God is revealed from heaven against all ungodliness and unrighteousness of men, who by their unrighteousness suppress the truth. For what can be known about God is plain to them, because God has shown it to them. For his invisible attributes, namely, his eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made.

Romans 1:18-21 (ESV)

Humans aren’t blind men. God’s eternal power and divine nature are clearly seen. And our move to suppress the truth that is plainly seen is on purpose. It is like six men and their twelve eyes with 20/20 vision, squinched tight, refusing to acknowledge the elephant while attempting to submerge it in a bathtub. Elephant? What elephant? I don’t see no elephant.

So if you have to sit through some Maoist struggle session at work put on by a Big Virtue consultant HR brought in, remember that the point is for them to inform you that you are, in fact, blind, and they are here on your behalf to describe the social sculptures as they really are. Maybe the intro wasn’t as oblique as I supposed.