Introduction

Every now and again you bump into a strange idea in the marketplace, usually in some side street thrift shop of discarded thoughts, and it comes to changes your relationship with the entire universe. I don’t remember exactly the circumstance that brought me to Walker Percy and his study of semiotics, but the thoughts were as fresh and cool as the other side of the pillow. It was like stepping through some access door to to the backside of language and everything in the world and the code I used to understand it was slapped on the table and dissected. It was gross; it was fascinating.

Okay, semiotics, what is that, some kind of robot sex or something? Nope. Semios is the Greek for “sign”; semiotics is the study of signs, particularly, what the signs mean. Put another way, it is the study of meaning-making. Or to use Percy’s definition, it is the study of signs and the use of them by humans.

The study of semiotics takes us back to the very beginning of Mankind’s time in the Garden, and deepens our understanding of what it means to be, and not to be, an image bearer. Even deeper still, it precedes the universe since we have a Creator who calls himself the Logos – the Word – and words have meaning.

Since semiotics is a foreign term to most, this will be like paving a landing strip in the middle of the Congo, which is to say, it will take some groundwork. I fully understand some may rather drill screws through their toes than engage with a word as dry as semiotics. But if you will bear with me, and with Percy, it will pay off. Today, the goal is just to move earth and pave a runway which I will land some planes on in future posts.

Semiots

To be human is to be a semiotician – a meaning maker. Every moment of your life you engage with semiotics, whether at a bar, a board meeting, writing in your journal, or talking to yourself. We are all semiots. Not only are you able to understand these sentences I am writing (the vocabulary, parts of speech, grammar, intention, tracking ideas, etc), you are conversing within your mind on their veracity, using signs and symbols.

Humans share the objective world. You and I, through our senses, experience the world that is there. We also have an internal representation of that external world within our minds. In the external world you see a mountain, and have a corresponding concept of “mountain” in your mind made of images, personal experiences of mountains, and the English word

m-o-u-n-t-a-i-n, made up of eight Latin letters arranged in a certain order. This is true of everything in your world. Percy calls this the umwelt – inner world, though I don’t know why it has to be German. The means by which these external realities can be transcribed into your mind is through the activity of naming. Naming is the beginning of meaning making.

Of course, we do not only share a world of physical objects but ideas as well. Unicorns do not exist, but the idea does. Marxism also is not something that can be handled or punched, but it is “real” nonetheless and as such is subject to the same semiotic principles as physical objects.

Children are the most active semiots. Once able to ask questions, their inquisitive minds are busy manufacturing an internal representation of the world by badgering their parents for names. “What is?…Where is…? Why does…?” etc. Parents supply the raw material of the names and explanations that the child takes in and builds the world of the mind. This experience is fascinating and at no other point in a human’s life is their minds busier world building than in childhood.

The moment an object is named for the child, his experience and observations of the object are wedded to an identifier. For example, a three year old sees a shiny red object that appears to be floating when the rest of the objects in his tiny world seems to fall towards the ground. It moves at the slightest breeze and doesn’t seem to like being touched. If it weren’t for the dangly thing tied to its bottom, it would be ungraspable. It is smooth and slick when he tongues it, makes a squinchy sound when he rubs it, and scares the bejeezus out of him when it suddenly disappears with a loud noise. He wordlessly inquires after the object with a point and a quizzical look. His dad names the object for him, “b-a-l-l-o-o-n”.

Mouthing the word, his mind fits the object into the word and how the word is stuffed into the object. That is “balloon”. The child has captured the object with a name and the idea and identity of the object has been captured by the child through the naming of the object which is now forever part of his umwelt.

In the future, when his parents ask him if he wants a balloon, he knows to what physical object in the external world it is referring to. “Balloon” has meaning; there is an internal representation in the mind of an external reality, and this is piloted by the profound and mysterious process of naming.

On a most basic level, this is what being a “meaning maker” is. We name things. You have names for everything and most of them are not physically present in your environment and have zero physical effect on you. A zebra, the Battle of Antietam, Pegasus, and World War III are all names of meaningful concepts even though they are either not present, or in the unreachable past, or fictional. Everything in your world is named. There are many things you do not know simply because you are unaware of their existence, though you do conveniently have a name for this absence in your world – you call it the “unknown”. The name “unknown” is a broad category that encompasses all things that are gaps in your world, even the gaps you don’t even know exist.

There is nothing that exists to which mankind has not assigned a name. Naming is the introductory handshake that begins the process of knowing. There is nothing you say, see, write, read, watch, or listen to that is not a string of objects or ideas with names that have meanings which have internal representations in your inner world. Or to put it simply: everything means something.

An exercise in semiotics you are familiar with is in advertising. The actor in the commercial for moderate to severe arthritis, with the medication name that sounds like something Biden would mumble in a speech, is chosen because the director intends for the age, gender, appearance to mean something to the intended audience. He or she is shown rubbing sore knees with a furrowed brow before the medication, and smiling with her grandkids on the playground after, all because of semiotics, because of what it means. Propaganda is another example that is absolutely dripping with semiotics. These are some of the more obvious applications we can connect with.

Let’s lift up the hood on this car and see how the engine turns, shall we? I am going to be approaching the ideas of semiotics from a materialistic perspective since this is how Percy approaches it.

Diads and triads

For most of the 14 billion years of the cosmos, there was only one kind of interaction between entities: cause and effect. One atom bumping into another, sunlight kickstarting photosynthesis, the gravitational tug of the moon on tides, electromagnetic forces keeping squirrely electrons in their orbits – all of these are a string of causes and effects. Though each of these interactions are very different, they can all be reduced to essentially the same relationship between two objects and can be symbolized as:

A ⇄ B.

Even in the vastness of the cosmos and the myriad interactions occurring, the relationships can all be reduced to this basic interaction of A causing an effect on B and vice versa.

The fancy name given to these types of interactions is dyadic interactions – diad meaning “two”. This just means a cause-and-effect interaction between two things. Dyadic interactions are also explanatory even if the interaction is complex, involving many steps, like the mouse that knocks the pebble that starts an avalanche that dams a stream that scares the fish; as many links of this chain of events as may be, they are all A⇄ B interactions and nothing more.

After several billion years of dyadic interactions on the cooling planet Earth, chemical interactions magically gave rise to living organisms, like amoebas. The amoeba maintains an internal homeostatic environment through dyadic interactions (protein synthesis, lysosomal activity, etc. – all A⇄B chemical interactions). An organism’s interaction with its environment can also be described as dyadic, such as a plant growing towards the sunlight. It doesn’t matter how increasingly complex these critters are, all internal and external interactions are still just plain old dyadic, A⇄B interactions.

This also includes organisms interacting with other organisms as part of their environment: an amoeba searching for a juicy algae, or a seductive bee dancing the coordinates of a pollen cache – it’s all dyadic folks. The image to the right is from Percy’s book and shows how all inter, intra, and extra interactions are cause and effect.

So what we have is an organism interacting with its environment, the object on the other end of the arrow. Some interactions have an obvious effect (a plant growing towards the sun) and some do not (the gravitational pull of Jupiter on a racoon in your back yard). Those interactions which do not have an observable, causal effect on the organism are ignored. This leaves “gaps” in the organism’s environment, meaning there is a cause and effect interaction present, but undetectable and therefore functionally non-exist; where there is no felt effect, the cause is superfluous. This “gap” is going to be an important concept. We will revisit it below.

Thus went the world and all interactions therein for eons, until the strange and mysterious bipedal creature came about -the homo sapien– and his use of signs.

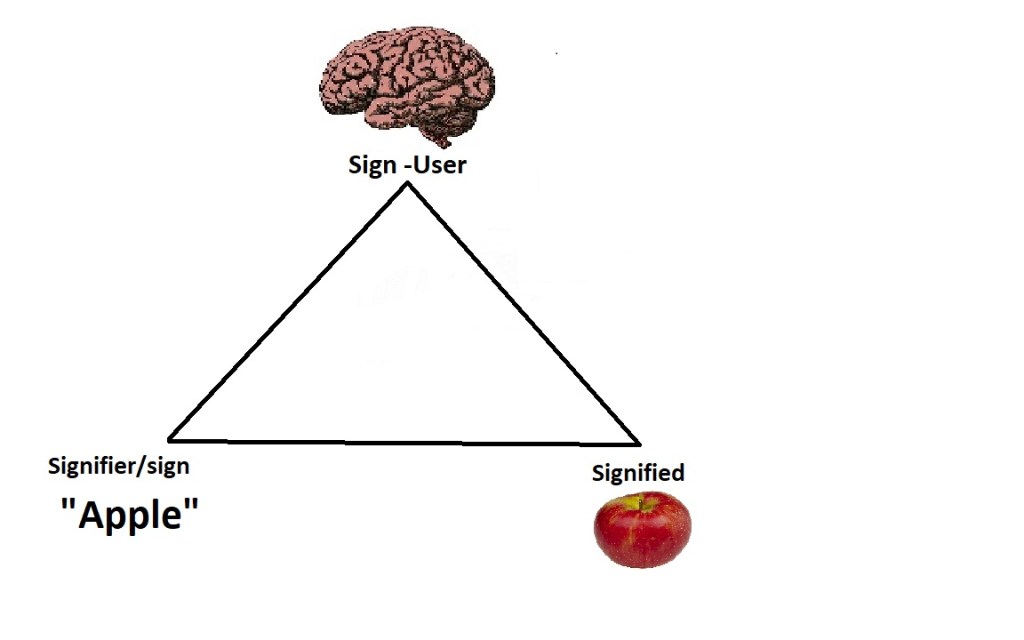

The advent of human language is a wholly different kind of interaction than dyadic. A new thing has happened, a novel monkey wrench was introduced – the sign. Signs are representations of things that may not immediately be present. Percy calls interactions involving signs a triadic event – as the name implies, it is triangular. Triadic events occur when “a sign given by organism A is understood by organism B, not a signal to flee or approach, but as referring to another segment of the environment.”

For example, when I hear the spoken word “apple” I understand it as referring to some other portion of my environment that may not immediately be present. It is calling me to reference the mental representation of the physical object that I have in my inner world of signs. It is not dyadic in the sense of me seeing a juicy red apple on the counter and my mouth drooling in preparation for a crispy bite, neither does it alert me to a predator, or signal a female is ready to mate. “Apple” is referring to a gap in my environment because there is no apple in the vicinity. The word is a stand-in for the actual, physical, appley thing.

As you would assume, there is some technical jargon Percy uses to keep all the categories clear. Using the above example, the word “apple”- either spoken, written, or a drawing of an apple- is called the signifier or sign, while the actual object the signifier is referring to is called the signified. Lastly, completing our third point on the triad, we have me, the observer – the meaning maker, the sign user – who hears this strange signifying vocable and knows it to mean an apple.

Percy uses the example of Helen Keller, whose dark and silent world was pierced with the light of symbols through her unflappable and patient tutor, Miss Anne Sullivan. After many failed attempts to link a symbol and an object, the concept clunked into place one day while water was flowing over Helen’s tiny hand while Miss Sullivan spelled out W-A-T-E-R in sign language into her palm. The magic of shaped fingers in arbitrary sequence depressed into her palm, which before was so much clutter, suddenly took on a meaning. There was nothing about shaped fingers in palms and wetness that satisfied any dyadic cause and effect relationship. The light that dawned on Helen’s mind was that Miss Sullivan’s finger letters, in some way, named an object/experience. The finger sequence was water. The cool, splashy, playful, ungrabbable thing had a name. Once Helen made the connection between the sign language spelled into her palm as referring to another object, she was invited into a whole world of meaning and ideas – she became part of her world, and the world was internalized within her mind through the symbols.

Sitting at my kitchen table looking out the window, I see a world that has been named for me. Sky, cloud, Sun, cedar post, tree, rabbit, car, mountain, grass, chicken, shed. I share this external world with you. We also share a highly similar, though not identical, inner world through the symbolic representations of this named world. The items I listed above call up the objects they represent in your own mind. “Cloud” means pretty much the same thing to us both. Because of this shared symbolic world, I can share with you my ideas, perspective, and creativity.

Triadic behaviors are social in origin. I cannot know what a sign is until I am given it by another sign user. In other words, every transaction of triadic communication requires a giver and a receiver. My wife recounts how she taught her younger brother that a tomato is called a “tonomashu”, which he took as gospel truth, right up to the day he was laughed at by his first-grade class when this trick was revealed. All signs are passed down or passed on from one meaning maker to another, from sign giver to sign user.

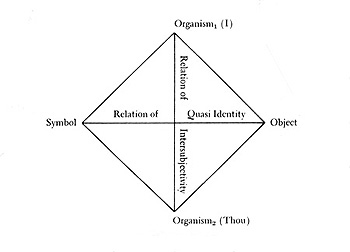

Any conversation between two individuals is a string of signs, each of which needed to be named for us. A bunch of symbols strung together is called a sentence which increases the complexity of the information I can send to you. We don’t just speak in nouns – cow, fence, grass, etc – but can also dress up the nouns with actions and modifiers to share creativity and sharpen the idea in the mind of another – the “green cow jumps.” This interaction between sign users is called intersubjectivity.

Percy says humans are “intersubjective beings” which he defines as “that meeting of minds by which two selves take each other’s meaning with reference to the same object beheld in common.” This is another fancy word, but it just means that we both share an external world and thus have shared signs to populate our internal representations of objects. This intersubjectivity transcends time and space, easily observed by the fact that as I write this you are there and I am here, you are then while I am now.

Intersubjectivity adds another point to our triadic environment turning it into a tetrad, where we can relate to one another by references to the objects in our shared world with our shared symbol. You and I have been relating intersubjectively this whole time, and you didn’t even know it!!

In this interaction between me and you, we are a namer and a hearer. This is true if we have a shared vocabulary, but becomes more salient when the namer introduces the hearer to a new word or concept. There are no solo namers out there. No one can hear what is not first named. Every act of naming presupposes an act of hearing. This means I cannot think of myself without us all thinking together, since I am using the named objects of my world that have been provided for me. Percy says, “I am not only conscious of something: I am conscious of it as being what it is for you and me.” To know something is to know it in community, to be co-namers and co-hearers, givers and receivers of symbols and meaning.

We lose track of the complexity and magic of intersubjectivity, naming, and meaning, because we swim in it every day, all day. Even in our dreams, we have no repose from this, as dreams are nothing if not subconscious emotion made symbolic.

It is through the act of naming that identity is conferred. This is a crucial concept and goes to the heart of each one of us. To be an individual is to be named. Naming can happen in a number of ways, both good and bad, which we will get to in the future.

The Lost Self

Thats the basics of semiotics – everything means something and we humans are co-namers and hearers of our shared world. Through the triadic interactions we know our world and build an inner galaxy of these objects, ideas and concepts. Every object has a name and can be referenced with a sign that you, the semiotic self, can envelope into your world. Everything, that is, except yourself. This is the precipice Percy leads us to; this is the hidden curse of being a sing user. A hidden sadness lies at the heart of all semiots.

Percy says the “fateful flaw in human semiotics is this: that of all the objects in the Cosmos which the sign-user can apprehend through the conjoining of signifier and signified, there is one which forever escapes his comprehension – and that is the sign user himself. Semiotically, the self is literally unspeakable to itself.”

A man can know more about the Crab Nebula in ten minutes than he can know about himself after spending his whole lifetime inside his own head. Why is this? Why is it, Percy asks, that when we see a group picture we are in we immediately look for ourselves first? Do we not know what we look like? Indeed, what does it even mean to know me? Can I know myself in the same way that I know the Crab Nebula or Rhode Island or a saltine cracker? What is a Tim?

The answer lies buried deep in semiotics, naming, identity, and image. In a time of unprecedented lostness, where identity is built on shifting dunes, we need to dig to the bedrock of identity, which means a visit to the Prime Namer.

Conclusion

I will leave you with a quote from Percy. In the next post in this series I want to brood over the process of naming- its magic and its despair- which will rehearse some of the semiotics learned today, and delve into the ancient things we find in deep Genesis and beyond.

With the passing of the cosmological myths and the fading of Christianity as a guarantor of the identity of the self, the self becomes dislocated, … is both cut loose and imprisoned by its own freedom, yet imprisoned by a curious and paradoxical bondage like a Chinese handcuff, so that the very attempts to free itself, e.g., by ever more refined techniques for the pursuit of happiness, only tighten the bondage and distance the self ever farther from the very world it wishes to inhabit as its homeland …. Every advance in an objective understanding of the Cosmos and in its technological control further distances the self from the Cosmos precisely in the degree of the advance—so that in the end the self becomes a space-bound ghost which roams the very Cosmos it understands perfectly.

Walker Percy, Lost In The Cosmos