Over Christmas, my family read the story of Christ’s birth from the book of Luke. We tend to hop back and forth between Luke and Matthew, each account having their own peculiar viewpoint of the nativity tale. Each also has that tedious but necessary genealogical portion that tracks Jesus’s ancestry through his earthly father Joseph to Abraham, in Matthew’s case, and back to Adam in Luke’s gospel. Even the most obtuse reader will recognize no small difference between the two ancestries.

Having such differences between the two family trees, which we will look at presently, leads to accusations and speculation of speciation and fabrication on the part of the gospel writers. After all, why else would the same person’s ancestral tree look so vastly different from the only two historical records available unless they were simply bogus? You would never see this kind of negligence in social sciences today, where we use swabs of people’s spit to track every twiggy bifurcation in a person’s ancestral tree dating back to the Fertile Crescent.

This is a prime example of CS Lewis’s chronological snobbery, assuming that we know better than the dumbos of two thousand years ago, who thought the Sun circled the Earth, because we have the scientific method that brings us the truthiest way of seeing the world. Never mind the fact that there are way more flat-earthers today than there ever were then.

So I want to make a few observations of the genealogy, both for its own fascinating sake as well as to show that sometimes there is a way to show a deeper truth than superficial scientific accuracy. And since tomes have been written about these genealogies, I will not retread well-worn paths.

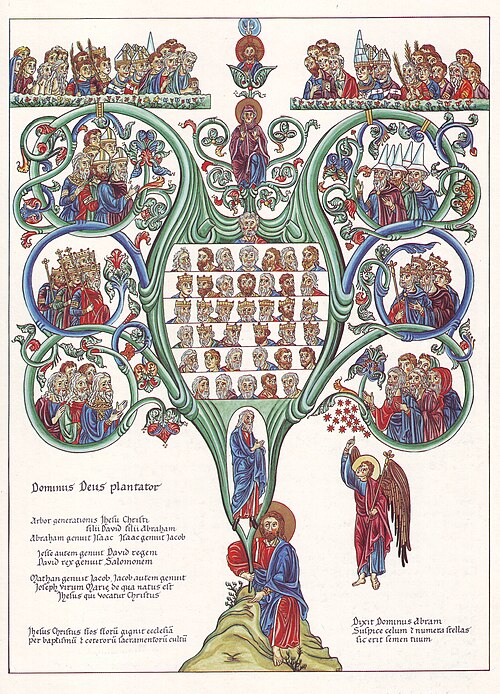

Matthew’s genealogy traces Jesus’ ancestry, starting from Abraham, through David, and then through David’s son Solomon, up through the centuries to Joseph, Jesus’ earthly father. A total of 42 names are identified, and they are curiously split into three groups of 14: Abraham to David, David to Jechoniah (the last surviving king in David’s line to hold the throne before the Babylonian exile), and Jechoniah to Jesus. Roughly, Matthew’s three groups of names track Israel from its start in Abraham to its height under King David, from its height to its nadir in Jechoniah, and from its dismal low point to the planting of Abraham and David’s true Seed in Christ.

Luke takes a different approach, starting with Jesus and climbing down the branches and trunk of the family tree all the way back to Adam, the son of God. At first glance, Luke’s seems much more uniform and more like what we would expect a genealogical record to look like. A tedious count reveals 77 names in the genealogy. Is this record precise, in the way that we moderns would consider complete and accurate? We cannot say for sure. Other than Matthew’s, we have no record for comparison. But if there are some omissions, which, according to biblical scholars, seems likely, then that means Luke pared back his genealogical record to 77 for a reason.

But immediately, we smell something fishy. Luke’s family tree stands much taller than Matthew’s. And the branches of Luke’s ancestry from David to Jesus twist differently. What are they trying to pull? Don’t they know we can count? Don’t they know that, for us to believe them, we need full disclosure of the hard facts?

Theologians and apologeticists have handily subdued the snarky responses to these differences, and I will not rehash those arguments, which are equally formidable as they are satisfactory. What I want to do is bring in some interesting tidbits that illuminate some of the curious features, namely the interesting numerical rubric we see in each, and surmise what truth the author was trying to communicate through this choice. If we lay aside our snobbish modern axiom that precision equals truth, and allow Luke and Matthew’s artistry and intention to speak, we will see that they are trying to tell us a deeper truth, and in ways that are much cleverer than clunky historical genealogy.

First, why did Matthew prune the genealogy into three groups of 14, haphazardly tossing out a bunch of names to get to this specific number? To understand this, we need to understand gematria. Gematria is assigning a numerical value to a name, word, or phrase, and was a very common practice in antiquity. Greek, Hebrew, and Latin each use the same characters of their alphabet for numbers, and so the “value” of a name could be determined by adding up the numerical values of the letters. English speakers are generally unfamiliar with this, having a Latin alphabet with Arabic numerals, unless you learned Roman numerals in middle school (L=50, M = 1,000, C = 100, etc).

So gematria was a sort of game, but also a base form of encryption. In Revelation, John identifies the Beast as one with “the number of a man,” and that number is 666. Using gematria, John’s readers would have decrypted this as referring to Nero Caesar, the wicked emperor torturing and torching Christians. To this day, there can be seen a bit of ancient graffiti on a bridge in Pompei where some lovestruck whelp chiseled, “I love her whose number is 545.” Cute.

Using this numerical game, we see that Matthew’s use of the number 14 is the sum of adding the Hebrew letters of the name “David.” David in Hebrew (דוד) is composed of the letters dalet (ד = 4), vav (ו = 6), and dalet (ד = 4) for a total of 14. Matthew structures his genealogy to include three sections (three symbolizing the divine number), each with the numerical value of the archetypal king of Israel. Writing specifically for a Jewish audience, we can imagine that Matthew’s choice would not have escaped the obvious alterations he made to the list, and even readers would perceive the truncated genealogy arranged as it was to be screaming to them that Jesus is the promised King, the shoot of Jesse.

In Luke’s genealogy, we have a different interesting numerical value: 77. Any Bible reader knows the Bible loves the number 7. The Revelation of John records over fifty references to the number 7 in one book alone. It symbolized divine order, completion, and perfection. And so Luke, a physician and one of the most precise ancient historians, uses seventy-seven generations from the first Adam to the second Adam, Jesus, to symbolize the completeness of the redemptive story. Adam is where mankind fell into sin, and the perfection of God’s salvation story is complete in the Second Adam, Jesus Christ. Writing for a gentile audience, by tracing the genealogy back to Adam, Luke includes the Gentiles in the ancestral tree, where Matthew only follows the Jewish line. As in Matthew’s list, Luke uses the truth of Jesus’ genealogy to twist it into a shape that reveals a greater, deeper, more glorious reality.

But Luke may also have another easter egg hidden in his genealogy. In Second Temple Judaism, the Book of Enoch was an important text, one that first-century Jews were very familiar with. Though it is not part of the canon, the Bible does quote from it (Jude 1:14-15) and reference it (1 Peter 3), indicating that the readers of the epistles were familiar with it. It is an odd book to be sure, but there is at least some truth to it, or else the Bible would not have quoted it.

Here is the relevant quote from Enoch

And the Lord said unto Michael: ‘Go, bind Semjâzâ and his associates who have united themselves with women so as to have defiled themselves with them in all their uncleanness. And when [the Watchers] sons have slain one another, and they have seen the destruction of their beloved ones, bind them fast for seventy generations in the valleys of the earth, till the day of their judgement and of their consummation, till the judgement that is for ever and ever is consummated.

The Book of Enoch, 10:11-12

According to Luke’s genealogy, there are 7 generations from Adam to Enoch, during whose lifetime the Watchers (disobedient angels who mated with women) spawned a race of giants, the Nephilim, whose wickedness led to God’s destruction of all life on earth in a great Flood. From Enoch to Jesus, seventy generations, yielding a total of 77.

Is Luke also alluding in his genealogy to the doom clock for the fallen angels waiting for their final sentencing at the advent of Christ? Scholars are split. It does strikingly coincide with the Book of Enoch’s timeline, and echoes similar sentiments from apostolic writings such as Jude and Peter. No reason to be dogmatic about this little morsel, but it sure is savory.

So Matthew included many names that were legitimately in Jesus’s downline, showing that He actually did descend from David and Abraham, but formulates it in such a way to reveal a more profound truth that Jesus is the Messiah, the Seed of Abraham, the true King of Israel. And Luke includes exactly 77 names, tying Jesus back to God, including the Gentiles, and revealing Christ as the beginning of a new race of man, all while (possibly) nodding to the denizens of the spiritual world that their destruction is nigh.

In our 21st-century view, this manipulation doesn’t make much sense. To us, precision is truth. If we can measure it, count it, weigh it, see it, and smell it, then we can determine the truth value. And so when we encounter Matthew’s seeming hack job of an ancestry, we snobbishly conclude he must be obfuscating something, and if an author is this helter-skelter with something we can check against history, how can we trust anything else he has to say?

All this serves to do is reveal our own ignorance of historical structures and demand that all truth be reformulated into the kind of information that can be tabulated, filled out in triplicate, and submitted through the proper channels. Not only is this way of thinking ignorant, but it is boring. To this stuffy approach to truth, the authors of the Bible lovingly invite us to dismount our high horse and swim in the deep ocean of truth that we have access to when we set aside our very tiny sliver of flotsam we cleave to.