Introduction

Somehow I escaped formal logic in high school. Perhaps it was because my graduating class boasted more pregnancies than diplomas, or maybe my head was too cloudy with hormones at the time to remember. But I am paying for it now because my son it smack dab in the middle of Ps and Qs, Ts and Fs, not to mention a fistful of latin phrases formal logic adopted.

One such latin phrase is modus ponens. It is a mode of reasoning from a hypothetical proposition to establish a conclusion. It follows the format:

If A is true, then B is true.

A is true,

Therefore, B is true.

Here is a real life example:

If Socrates was mortal, then he was a man.

Socrates was mortal.

Therefore, he was a man.

“If Socrates was mortal” is called the antecedent and establishes the conditions upon which the consequent “then he was a man” will be considered true. This conditional logic is so common it was given a name, modus ponens, just like certain dance moves are so commonly seen at weddings they are given names, like the Roger Rabbit, the Electric Slide and the White Man’s Overbite.

We all use modus ponens daily, and as illogical as we can be from time to time, we all understand implicitly the connection of conditional logic. Conclusions will follow from premises that are assumed to be true. Every antecedent has a consequent.

Sometimes, however, we can be so caught up with antecedents and proving our premises that we don’t look down stream far enough to see what exactly the conclusions will be, or if we will like them when we get there. One man who knew his modus ponens was Friedrich Nietzsche and his protege Adolf Hitler. Nietzsche composed the modus ponens and Hitler gave it a beat to could goose step to. Both were able to follow the logical flow of the premises the West was adopting far better than their contemporaries – far better than our contemporaries. And it wasn’t a happy time.

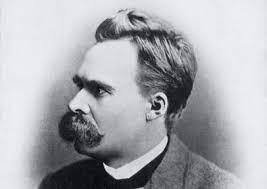

The Mustache and the Madman

Friedrich Nietzsche was only slightly less famous for his atheistic nihilism than for his epic mustache. I mean, just look at that dirt squirrel! It is a thing to behold. Makes me wonder if he filter fed like a baleen whale, catching small crumbs in the thick bristles to munch on during an afternoon of deconstructing western civilization.

Most people are familiar with his “God is dead” declaration found in his Parable of the Madman, which you should read tout suite. He was a nihilist, though this served to invigorate him to squeeze life’s juices even harder, resulting in some killer one-liners that romanticized life and the peculiarity of existence.

Recently I read Nietzsche and the Nazis: A Personal View by Stephen H.R. Hicks. It was short, succinct, and a fantastic overview of the Third Reich, Nietzschean philosophy, and how they tied together. You can listen to it in a brisk 3 hours, and what better way to spend your time than dissecting the brain worm that is eating out the bright apple of the West?

This Time It’s Personal

Full disclosure, I have not read all of Nietzsche’s stuff. What I have read I find intriguing. The man was a wit, and no two ways about it. Few people, particularly atheist philosophers, follow their premises to their logical conclusions, and Lil’ Freddy does it with what can only be described as ungoverned perspicacity. When you study apologetics for long enough you sort of get the gist of what he was about and come up with some retorts to the pijama atheists who paused their game of Diablo to respond to a discussion forum. Do you sense a but coming on…?

But, as I was reading this book it became clear that I took Nietzsche far too lightly, or rather I did not see the footprint for the foundation he was digging out was precisely the dimensions of a certain ziggurat one might find in the region of Babel. What rebuttal I had to his philosophies seems now to be on the level of knuckling up for a schoolyard tussle when I ought to have been preparing for a school shooter.

To The Book!

Throughout his writings, Nietzsche wrestles with an impatience for his fellow man. Growing up in the middle of the 19th century, where man was quickly becoming the hero of his own story, there was a wistful and feverish yearning to see mankind grow up into maturity and take his place in history. But the one species that had slithered its way up the evolutionary ladder to dominate and subjugate all other species seemed stuck with this entrenched idea that there was a transcendent God dithering about in the backs of our minds. This simpering faith restrained the fullness of human potential with silly and useless beliefs about themselves and morality; beliefs which kept their legs weak, their eyes dim.

Pious peasants of the medieval era were excused of such beliefs: when your life was short and you had little knowledge natural phenomena, belief in God is understandable. Safety, security and comfort was what was needed, and God quelled the quaking of man’s soul. Belief in the afterlife helped you get up on a Monday morning to endure a sucky, short, subsistence life.

But those sympathies could not be extended to modern man. The 19th century was a massive editing of God’s job description. Darwin’s On the Origin of Species was published when Nietzsche was fifteen and many areas of scientific study were describing mechanistic explanations for phenomena that were once attributed to God. No thinking person should still cling to such archaic and superfluous beliefs which ran afoul of what the senses were telling us. What Nietzsche intended to do was rouse modern man with a sobering slap to wake him from his spiritual stupor.

Hicks uses the analogy of a child being woken in the middle of the night and told both her parents had died in a car accident. Suddenly, she is thrust into a cold, dark and lonely world, where all comfort and safety was gone. This is how Nietzsche intended his famous phrase “God is dead” to land. We are alone. Our source of comfort and meaning is dead. Ready or not, we are left to our own wits to make our way through the world.

Such a bold and rash approach was brave, and bravery would be needed for this strange and unprecedented march into the future night. The ramshackle sheepfold of Judeo/Christianity must be left behind, and with it the comfort of green pastures and whispering waters.

Judeo/Christianity, after all, was antithetical to what Nietzsche believed to be man’s destiny. Christianity wanted us to share. Be kind. Be good little boys and girls. Take care of the weak and needy. Reject your natural desires. Keep the sick alive. And if, in the end, we are weak and meek enough, we all would fly to a utopia where competition would finally be over, and the lion and lamb would spoon in a quiet pasture. All of this hogwash was predicated on the fear of death and man’s helplessness in the teeth of it. With a guarantee of bliss in the sweet by and by, the licking of the collective wounds kept humanity content with mediocrity and safe from the reality of our terrible possibilities. Nietzsche was surrounded by the abandonment of potential and the praise of Sunday school morality.

Then again, there were exceptions. Every generation seemed to birth a self possessed champion who embraced power and bravely faced the harshness of life and the certainty of death. These were the Julius Caesars and Napoleons, the Khans and Charlemagnes, who did not reject their will to conquer in exchange for the scraps of temporal cures to the problem of death. How was Nietzsche to reconcile these masters with all the slavish, simpering religiosity?

Biology was the key. Nietzsche was a plucky fifteen when Darwin published his tome. Darwin laid out the case for man having been arrived at through a mindless process of genetic variation and environmental fitness. This theory applied to all organisms that live and ever had lived, all united in a perpetual round robin tournament of inter and intra species competition for resources and life. Darwinian mechanisms were evident throughout history with massive empires rising and consuming their rivals only to be consumed themselves by the next fitter, stronger superpower. The grand motif of life was the macabre dance of predator and prey.

Nothing was more obvious to Nietzsche. In nature there are two types of animals: herd animals and predators, sheep and wolves. Sheep huddle together in a commune of safety, and the wolves prey upon them. This distinction was “decided” upon by nature, which does not assign moral categories, and each creature lives out the nature it was given, each plays its part. A sheep cannot become a wolf and a wolf cannot become a sheep. Given the premise that humans are animals, Nietzsche concluded this divide ran through humanity as well.

Each human could be identified as a sheep or a wolf by their biologically determined traits. The predators are masters: bold, creative, assertive, courageous, reckless. They are risk takers, free thinkers and rebel from social pressures. Conversely, the sheep are passive, meek, cooperative, forgiving, passionless. They rely on the health of the herd as the primary means for their own survival, even if it means keeping the weak alive, since at any time they may be the weakest. Given the antecedent of Darwinian evolution, Nietzsche identified the consequent that all human behaviors are biological in origin. Could any thinking modern man see it otherwise?

Morality, therefore is not transcendent or immutable, but derivative of the underlying biology. If you are a sheep, “good” would be what comes naturally to sheep: staying in the flock, strength in numbers, green pastures, communal living, skittish towards the unknown, wary of potential danger, etc. Those traits which sheep are naturally averse to, but which come naturally to wolves – prowling, mavericking, preying – would be “bad”. Wolves on the other hand would call “good” what came naturally to wolves. It is not bad to eat sheep, if you are a wolf; in fact, it is quite delectable.

“Good” is merely those behaviors which come naturally to weak herd humans, so they can compensate for their weakness and survive. The question is not whether a certain moral value is eternally or universally good, but rather what kind of person finds this value to be valuable? As Hicks puts it, one’s moral code is a function of his psychological make up, and his psychological make up is a function of his biology, and therefore all moral codes are a strategy for survival.

Nietzsche believed that in our evolutionary past wolfish character traits were praised while the meek and lowly occupied the bottom rungs. Through a series of events, this lesser man’s morality came to occupy the prime time and suppressed the more aggressive, true, and instinctual wolf. And here is where he got real pissed. Which of the moralities, the sheep or wolf, would lead naturally to humankind’s greatest potential? You can guess, it’s not hard. For the sake of making it real obvious here are the two options as he saw it:

Wolf: Assertive, strong, fierce, bold, brave, risk taking, ambitious, unafraid of death, ravenous, drive to power, intrepid, free thinking, conquistorial, overcome weakness, embrace instinct, self first.

Sheep: Praise meekness and gentleness, strength in weakness, outsourced strength, afraid of death, sacrificial, forgiving, kind, submissive, anxious, self restraint, self denial, disgusted by desire, deny instincts, keep sick alive, depend on others, crave safety, consider others as better than self.

I trust the answer is clear, at least according to Nietzsche. What ire, then, when a man of wolfish compulsion lived in a world where sheepish morality ruled! To deny humanity it’s historical triumph and bold future in exchange for a simpering, weak and pining religion was the only true evil that existed. What we needed was a new morality, a morality beyond Judeo/Christian standards – something beyond good and evil (the title of one of his books). Traditional morality, paradoxically, had become a bad thing. Given the premise that mankind is destined to reach its highest potential, Christian morality was in direct controversion to this biologically determined goal and therefore wicked.

How did the obviously dominant wolf nature become subdued to sheepish morality? He saw Judeo/Christian morality originating from Israel’s slavery in Egypt. In order to survive in a slave culture, Israelites had to deny ambition and reject retaliatory impulses through practicing meekness and contentment with subsistence living. Revenge would get them killed so they resorted to forgiveness; submission meant survival. These values were taught to their children to increase their chances of survival, and so on, until a value system became entrenched.

For Nietzsche, the mystery of morality was revealed to be nothing more than the necessary survival techniques employed by biological organisms in the context of environmental pressures. When these responses to selective pressures become internalized over generations, they take the shape of an external moral code. Jewish Levitical law, then, is the codifying of survival techniques. Given the premise of Darwinian mechanisms, is there any other way to see it?

This sheepish code was handed down in perpetuity through Jewish traditions until Christ, from Nietzsche’s perspective, made it way worse by extending this slavish mentality into our thought life, not only our actions. At least a Jewish slave could murder an Egyptian in his imagination; Jesus said we couldn’t even have that satisfaction anymore lest we be roasted for eternity. Yet, foundations of all our current democracies are built upon these Judeo/Christian principles, which enable the weak to band together and survive, calling “good” which comes most natural to the weak, and “evil” that which threatens safety.

There are always more sheep than wolves in nature and the same is true in democracies. When the sheep get the majority vote, the wolves must develop a taste for chlorophyll or find themselves cast out of the camp.

Damming human greatness because of the sheepish majority was anathema to Nietzsche. The great engine of raw animal instinct and passion to conquer that catapulted homo sapiens to Alpha predator of earth was choked by the weak and insipid. Nietzsche’s yawp “God is dead” was as indignant as it was liberating. God. Is. Dead. And good riddance.

With this death knell, trepidation shivers through souls, exposing us to the void of mortality. But there are some men who rise at God’s death and quiver with solem anticipation of shouldering the burden of human destiny. If God is dead, they must become gods themselves to fill the vacuum left behind by divine decomposition and scrape value from the crust of the earth with their own strong hands. This kind of man will pull all mankind to a higher history; he will be the Ubermensch, the Overman. All the power of the Master types of antiquity will course through his veins. He would not be a creature who bowed to the worst of man’s weakness, but would be instinctual, ruthless, driven and glorious. He will be a “Caesar with the soul of Christ.”

Instinct is the Overman’s guide: passion and will. He embraces the nihilistic reality of life, and instead of groveling for religion’s false security, he grasps life by the ears and leads humanity into a brave future. History and biology has selected him to impose his will upon the others who are in a stupor of anxieties and pieties which keep them eeking through life. He will bravely lead humanity by the creation of new values and dominate others with those values for their own good, for the good of all humanity.

Given these bold meditations it is plain to see how Adolf Hitler was drawn to this throbbing power. He saw himself as an Overman and the Germanic race as the carrier of a new morality bringing humanity towards the mountain top of history. In one generation he would attempt to purify the human race from undesirables and establish new values which would live on in perpetuity. Darwinian evolution would become a tool in the hands of an apt master who had courage to steer nature’s power to align with his will.

Bringing It Home

Of course, Nietzschean nihilism is not sufficient cause by itself to explain Hitler’s genocidal craziness. Lots of people are nihilistic yet passive and quietly live in the folds of Judeo/Christian morality. But nihilism is a necessary cause. The conclusions of the Third Reich follow perfectly from the Nietzsche’s premises. If God is dead, then we must become gods ourselves. The Nazi phenomenon was a manifestation of this philosophy in the most cruel and ruthless manner. But have we seen the last of it? Was the Overman a prototype that failed, never to be attempted again?

If not, can anyone point to a good reason why not? We certainly have done nothing to alter our premises. Everyday millions of students are graded on their allegiance to the axioms which gave rise to the Overman – that we are star stuff, that above us is only sky, and that you, dear student, are a product of accidents and purposelessness.

But we have not made the connection. We cannot preach the dogma of purposelessness and evolution toward a higher humanity without someone eventually realizing the ramifications of these ideas. Somewhere there is an iron scepter lying in the grass lonely for an iron fist to grasp it.

This fact is unpleasant and so we try to place the square peg of Christian values into the round hole of atheistic ideology. We can still exist with such a stark contradiction is that no one has forced us to piece these unmatched worldviews together just yet. The reason we have been able to coast on the fumes of Christian values in America for so long is due to the steep downgrade of the road toward perdition.

But God cannot be mocked; we will reap what we sow. Conclusions will follow from our premises.

Conclusion

The consequent of the antecedent “God is dead” is a gaping void where anything is permissible. As Chesterton said, the danger of atheism is not that you will believe nothing, but that you may legitimately believe anything.

If God is dead, then what follows is a smorgasbord of sin. If God is dead, then might makes right, a fetus is a cluster of cells, purposelessness abounds, a man can menstruate, love is chemicals, truth isn’t real, goodness is arbitrary, selfishness is justified, certain races are favored in the struggle for life, make as much money as you can before you crawl under a head stone. Modus ponens, people. Modus freakin’ ponens.

The only thing which can match wits with Nietzsche is a robust worldview where there is a transcendent morality from a God who is a Creator and a giver of truth, who’s revealed to us what is good and evil. Morality is founded on the immutable nature of God’s eternal character, not the meandering, purposeless bright ideas of complex chemical reactions fizzing at 38° C that we call humans. The quickest way to dispelling all this rot it to reject the premise that God is dead. And it is not good enough to settle for the “God is a useful concept” idea that our scientific elites have very sweetly has allowed society to retain so long as we keep it on the mantle.

How about we present another modus ponens? If God is Living, then He is the Big Cheese and we must obey Him. What consequents follow personally and culturally from this antecedent?

You are an amazing thinker! And writer! Thank you and I hope somehow this message can be broadcast to our society before it’s too late.

LikeLike

Stephanie,

Thank you for reading and your very kind words.

LikeLike

This is some awesome stuff, Tim. Unfortunately the wolf will always win a fight against a sheep. But, at some point, he will do it in a way that the sheep doesn’t even know he’s about to die, and all of his sheep buddies will be too busy with themselves to notice. Or, maybe, he decides that simply eating the sheep is no longer satisfactory. Perhaps it is better to control the sheep to lengthen his control over their destinies…instead of simply ending it. End result=the same. Benefit to the wolves=twofold. The world today. It will not get better.

In the same sense…balance is what has arguably brought us to this point in time, in history. There is always balance, it’s just a matter of perspective. Positive and negative charges, gravity, equal and opposite forces, love, hate, good and evil…accepting both as valid arguments is to me understanding that siding with one side or the other is inherently wrong. One can simply not be without the other. Without good, there is no evil.

I’m definitely going to read more of this “thought butter” of yours…say, do you have any unsalted?

LikeLike

Austin,

Thanks for the response! The struggle between good and evil brings up lots of cosmic questions. Most notably is “Who says what is good and evil?” If there answer to that is not God, then all that Nietzsche said is spot on. Thankfully, God is good and it is from his eternal nature that we understand goodness, truth and beauty. But since God is an eternal being and there is no darkness in him, then good certainly can exist without evil.

In the spat Nietzsche had with God, I think I think a good way to sum it up is the following:

“God is dead.” – F. Nietzsche, 1882

“Nietzsche is dead.” – God, 1900

LikeLike